Millville rooted in several centuries, not just one

By Sam Harvey, Staff Reporter

“Story Used Courtesy of Coastal Point”

Historians may one day devote whole chapters to Millville. But at least in the time since the town was first established, some 100 years ago, there’s been little written about its origins specifically.

However, there are some very local and well-written histories which do, in illuminating the early days of the Baltimore Hundred (southeastern Sussex), cast many glancing rays upon the area where Millville would one day rise.

What record does exist suggests the community came together very slowly over time. Although Millville didn’t formally organize until early in the 20th century, quite a few local families can probably trace their ancestries hundreds of years earlier. Gordon Wood Sr., who grew up in Millville, traced dozens of local genealogies in preparing his “Letters to the Little Ones” family history. And in doing so, he made this observation: many of the names appearing in the 1780 Census for the Baltimore Hundred were still in local evidence years after the town’s establishment. Among the 30 students of Wood’s graduating class of 1953 from Lord Baltimore School, fully 25 students still bore surnames mentioned in 1780, or their mothers did, he pointed out.

Delaware was just a newborn in 1780 — it had taken the Calverts of Maryland and the Penns of Pennsylvania nearly 100 years of contentious, and sometimes violent, dispute to settle the borders. At one point, in 1737, England’s King George II had so despaired of the dueling property owners that he asked: “That they do not make grants of any part of the lands in contest … nor any part of the three lower counties, commonly called New Castle, Kent and Sussex, nor permit any person to settle there, or even to attempt to make a settlement thereon, till His Majesty’s pleasure shall be further signified.” (From Thomas Scharf’s “History of Delaware, 1609-1888”) Not that the area was all that appealing anyway. “When the first settlers had arrived, marshes and swamps covered much of the eastern portion of the present-day hundred (Baltimore Hundred), and early plantations were largely confined to high ground in the vicinity of the present towns of Ocean View, Millville and Clarksville,” Richard Carter wrote, in his “History of Sussex County.”

Some of the local farmers held slaves in those days, but “the economic viability of slavery … had diminished in this area before the (Civil) War,” Wood wrote. “By 1850, the U.S. Census reported almost 50 percent more free ‘colored’ males than slaves in Baltimore Hundred — 237 to 162.” When war came, the men of the Baltimore Hundred volunteered for the Union. Following Scharf’s history into the Civil War, Wood focused on Company D of the Sixth Regiment, Delaware Volunteer Infantry, and he noted many local names on Company D’s roster: “Lynch, West, Williams, Bennett, Bunting, Derickson, Evans, Hickman, Hudson, Megee, Murray, Rickards and Wilgus. Clearly, this company was recruited from residents of Baltimore Hundred and the surrounding area,” Wood pointed out.

They would serve a relatively short, but bitter tour, primarily as guards at Fort Delaware, “a dreaded prison for Confederate soldiers,” Wood wrote. Thousands of prisoners succumbed to conditions and disease, and he suggested that guard duty may have been almost as bad as being a prisoner.

This atlas shows the Baltimore Hundred, pre-1700. “There is no argument against Lincoln’s freeing the slaves,” Wood continued. But he noted the problems that followed the Civil War — the Jim Crow laws that slowed local progress toward universal civil rights, and the widespread economic side effects. “Untrained and uneducated and generally without land, the former slaves were ill-equipped to get ahead,” he wrote. “The last third of the nineteenth century was a time of little economic development.”

But this was apparently affecting everyone in the Baltimore Hundred, black and white. Wood reviewed 40 year’s worth of Sussex County tax assessments, leading up to 1896, and noted very slow appreciation among the estates of the Baltimore Hundred’s farming families.

Continue Reading

When they weren’t putting food on the table, many people cut timber, or ran sawmills to turn it to lumber. In fact, “A Guide to the First State” (Works Progress Administration), pointed out that Millville “grew up around a ‘steam mill’ (sawmill) operated by Capt. Peter Townsend in the late 19th Century.” Where the timbering cleared the fields, there were crops and livestock, and in the local waterways there were plenty of fish, crabs, clams and oysters. But as Carter described in “Clearing New Ground,” (a biography of Delaware Gov. and U.S. Sen. John G. Townsend Jr.), “the middle 1890s were years of recession…caused by the excesses of the railroad barons and the great Eastern financiers and industrialists in their quest for ever-greater profits. “The downturn came at a time when southern Delaware farmers and businessmen were just beginning to see the marvelous new opportunities opened up by the coming of the railroads, of which the new strawberry business was just one example,” Carter wrote.

He blamed poor roads, and a rail monopoly which levied “outrageous rates in areas like Delmarva,” for stunting Sussex’s economic growth. “The absurdly high rate schedules … were directed particularly at fresh fruits, seafood and other perishables, the very products which Baltimore and Dagsboro Hundreds and Worcester County produced in abundance,” Carter wrote.

Southwestern Sussex Countians were better off, in that they had access to a major alternative shipping route, in the Nanticoke River, Carter noted. Not so on the east side.

“Many Baltimore Hundred men tried to escape the railroad rates by shipping from Townsend’s Landing (now known as Sandy Landing), White’s Creek, and other Indian River shipping points, but that was a much less certain proposition,” he wrote. “The hazards of navigating the shallow Indian River Inlet and the mouth of the Delaware Bay were notorious.” But into the early 20th century, they continued to launch from the local docks and dodge the shoals, up the coast to Philadelphia and New Jersey.

Some of the ships were even built locally — Carter referenced Millville resident Elisha C. Dukes’ sloop, the “Ethel Dukes,” which had been built just north of Millville, at Walter’s Bluff (near Holt’s Landing). Wood’s research lent additional detail — the “Ethel Dukes” had been built in 1888, he found, and had been 41 feet long with a remarkably shallow draft (essential design for the shallow local waterways). “Sloops…and small schooners from 10 tons to just over 40 tons and ranging in length from 30 feet to nearly 60 feet,” Wood wrote, “sailed from such places as Daisey and Pennewell’s Landing in Ocean View, White’s Creek in Millville, Blackwater Creek and Millsboro.”

The Masonic Temple in Millville. He noted the gradual disappearance of these graceful craft in the wake of competition from the railroad, new overland roads and silting on the river and at the landings, with some regret.

The 20th century would bring radios and automobiles, prosperity and depression and prosperity again, and a million new technologies. But these were the times leading up to Millville’s establishment, 100 years ago. And these were the people who founded the town — families of ship captains and watermen, millers and farmers, many of them residents for hundreds of years already, in what would become the town of Millville. The tiny acorn has grown to a sturdy oak since the tiny town of Millville announced its presence in 1906, one century ago this year. And the children of those times have become the town’s elders. But they remember, and as copper leaves swirl back to the tree and green to bud again, their memories lead back to the days when Millville first put down its roots. The winters were apparently harsher in those days — as long-time resident Ruley Banks pointed out, the world had just emerged from the Little Ice Age, and he remembered some of the old-timers’ accounts of the “Blizzard of 1888.” “There was snow up to the eaves of the houses, and the farmers had to tunnel their way out to feed the cattle,” Banks relayed. “I remember a couple of elderly ladies, from Ocean View, who came to the school and talked about it — this was in the 1940s. They said a man had died in that blizzard, and they couldn’t get him out until the snow melted.”

But things warmed up eventually, and Millville started to regain some of the momentum lost during the depression of the late 19th century.

For the most part, the people of the still-remote Baltimore Hundred remained somewhat insulated from the up-ticks and downturns of the broader economy.

Millville locals subsisted much as they had for hundreds of years, digging ditches to drain new farmland, clearing ground, raising their crops and livestock and fishing the local waterways.

Life on the Farm

Long-time resident Pearl Robinson, born in 1921, remembered a simpler time — if not an easier one. “You had to work — too much,” she stated. “I picked strawberries and tomatoes, thinned corn,” she said. “I’d attend to the corn planter chain — that was used to hill the corn, and then you could harry it both ways.” “People worked the dirt,” added Grace Wolfe. “And everybody fished and crabbed — they set a good table.” But she suggested it had been difficult for people of her parents’ generation to get ahead financially. “Corn, soybeans, wheat – you could hardly make a living,” Wolfe pointed out. “It was chickens that put us on the map.”

Military Service

The teen years of the 1900s brought military conflict, first along the U.S.-Mexico border (in 1916) and then overseas, and the locals left their forests, farms and docks to serve.

Known as the Delaware Militia until 1906, the Delaware National Guard reformed as the 59th Pioneer Infantry in 1907. This combination infantry/construction engineering unit, seasoned along the Rio Grande, “served with honor” in France, and remained with the occupying forces in Germany until mid-1919, according to H. Clay Reed’s “Delaware: A History of the First State.”

Long-time resident Bill Cobb remembered one veteran – John Sanford Noble Sr.. He was always a little shell-shocked after the war, Cobb said, but did reenter civilian life, becoming a math teacher at the Lord Baltimore School and marrying the daughter of preeminent (and sole) local physician Dr. K.J. Hocker.

Surely there were others from the Baltimore Hundred who served — perhaps even some who reenlisted in the late 1930s.

World War II wrought significant changes, in Millville as elsewhere around the country. “Everything was hard to get,” Cobb remembered. “There were (ration) stamps for everything.” The locals made out better than people in some areas, he added — again, Millville residents had gardens and livestock, and so weren’t as dependent on the markets as some. “But there was nobody in Millville,” Cobb remembered. “It was pitiful — you couldn’t find anyone to talk to, unless it was an old man.” All the American men had gone to war, Cobb pointed out — as he would himself, as soon as he came of age. Some young men did arrive in the Millville area in the mid-1940s, though — Nazi prisoners, mostly captured in North Africa, according to William Connor and Leon deValinger Jr.’s “Delaware’s Role in World War II.” “In addition to solving some of the farmers and orchardists’ problems, Southern Delaware poultrymen declared the employment of the Nazi prisoners prevented enormous losses in their industry,” Connor and deValinger wrote.

Wolfe remembered their camps, south of Ocean View. However, she emphasized that the prison labor hadn’t filled the labor shortage. “There were a lot of women out in those chicken houses, too,” she noted. Women of that era took a greater role in direct support as well, through the Women’s Army Corps. And the older men volunteered for Civil Air Patrol guard duty, in the observation towers along the beach, Cobb remembered.

Millville United Methodist parishioners honored the veterans with a plaque, bearing 40 local names, including Banks, and his cousin, and Cobb and his brother, and two men apiece from the Marvel, Murray and West families, three from the Derrickson family and four Megees. Church and social life For the most part, social life revolved around family and church, with a little fraternal escape at the Masonic Temple (Doric Lodge), built in 1900. According to a church history written by Banks and Harriet McClung, there was another church in town before parishioners built the Millville U.M., in 1907.

The little building with cedar siding (still in existence today), across the street from the Doric Lodge, was at one time a Methodist Protestant church, later a Baptist church and was then used as a fourth-grade classroom, for a short period. A group of Millville U.M. parishioners bought it in the 1950s, and it became a hub for church-related social events, fundraisers, potlucks and Ladies Aid meetings. According to Banks and McClung, Millville U.M. had for many years been too small to rate its own minister — for many, many years, they shared with Mariner’s Bethel, in Ocean View, and Frankford and Roxana churches.

As long-time resident Grace Wolfe pointed out, “It was three weeks before we got a Sunday morning service.” So getting to hear a real sermon was a treat.

“They took their main collection the third Sunday in June, after school was over and when the first crop was in,” Wolfe added. This collection primarily went to organize a special children’s program, she said. And she remembered a minor scandal when it came to light that her father had accepted a donation from the liquor store — “That’s tainted money!” critics charged. But he apparently countered that he’d take a donation wherever he could find one.

Kent and Sussex were dry counties from 1907 until — well, some towns are still pretty dry. Suffice it to say, the locals were ahead of the curve when it came to temperance, adopting their own brand of Prohibition more than 10 years before the movement went national. Cobb remembered some other entertainments — including those provided at a Junior Order lodge, located due north of Millville United Methodist. “They held shows there, stage shows, maybe a singer and someone to play the guitar, and they’d sell you a 25-cent box of popcorn,” he recalled. There was also a pre-“speakies” movie theatre, at least for a short time, near Dr. Hocker’s office (next to the present-day Tri-State Coins & Firearms), Cobb said.

Everyone remembered Fourth of July celebrations at Sandy Landing (northwest of town, on the Indian River) as the highlight of the entire year. People set up stands and sold food and beverages; others just brought their own and picnicked, or had a fish fry. There were plenty of bonfires — even a firecracker or two. Grace Collins remembered fishing for crabs — “It didn’t matter if we only caught one, we’d split it.” As she remembered, no day had been complete until she and her brother had fallen out of the boat and utterly soaked themselves.

According to Collins, the main road through Millville was paved in the 1920s — but as native son Blaine Phillips noted, all of the side roads remained hard-packed dirt well into the 1940s. “Which was what made it such a wonderful place to have ponies and horses,” he said. Phillips remembered riding to school sometimes (just to show off), tying the ponies to a tree for the day, or riding out to the beach to consort with the Guardsmen who were patrolling on horseback themselves. He graduated from the Lord Baltimore School in 1948, but even then he said there still weren’t enough kids to put together a football team. The big sports were basketball in the winter and baseball in the summer.

Phillips remembered playing baseball in the lot in front of Amos McCabe’s store (due east of the Millville Fire Hall), against the boys from “uptown,” nearer to Clarksville.

Downtown

In the early days, downtown Millville consisted of four or five dry goods/grocery stores, a feed store and Dr. Hocker’s office. It would be a few years until the locals built a fire hall, but that block had always been the central gathering point.

Cobb remembered an old-fashioned fire truck (pull wagon with a pump) parked in the garage behind Dr. Hocker’s, and a hand-cranked siren above the doctor’s office — but even the hand-cranked siren was a relatively modern development. For years, people simply responded to the center of town whenever the bell at the Millville U.M. rang for two minutes straight.

Firefighters purchased their first motorized fire truck in 1936, and built the hall in the late 1930s, according to the Millville Volunteer Fire Company. It was, and is, situated on the lot where the local boys played ball, bordered on the west by the store run by Phillips’ father, Emmons, and on the east by the store run by McCabe (and later Robert Willey), to the east.

McCabe also had a feed store, right across the street from the fire hall, and Charlie Derrickson had a store where the Salted Rim is now located, between the feed store and Dr. Hocker’s. As Collins remembered, Derrickson was always willing to take fresh eggs or butter, in lieu of cash.

The lot where Dr. Hocker used to “pull teeth, sew you up if you got hurt,” as Robinson put it, has seen a few changes since those days. There was a store along the front for a time, where one could purchase patent medicines. Then the Palmatary family took it over and installed a soda counter, which certainly made it one of Millville’s big social gathering spots. The store eventually passed to members of the Winterbottom family, who ran operations from the original building, for many years.

Looking eastward from the downtown area, there were fields, and beyond, the schoolhouse that predated what is today the Lord Baltimore Elementary School. Children of all ages shared the old school, but high-schoolers moved into the new building once it was completed in 1932. For several years (until the old school was torn down) the buildings stood side by side, and elementary students continued to take their lessons in the classrooms closer to Old School Lane. Whereas the modern school is mostly over the line in Ocean View, the old school truly belonged to Millville.

Westward, past downtown, there was the store that belonged to Wolfe’s grandfather, Elisha Dukes, and then to her father, Harry Dukes Sr. Although the store burned in 1930, Wolfe remembered conversations with her father about the range of goods they sold — including men’s jeans for 50 cents a pair, “75 cents for overhauls.” Another Dukes family property survives, right next door (due east), where local artist Laura Hickman has opened a gallery. It was once a gas station — an Atlantic gas station, and apparently another popular hangout for Millville youth probably up to no good.

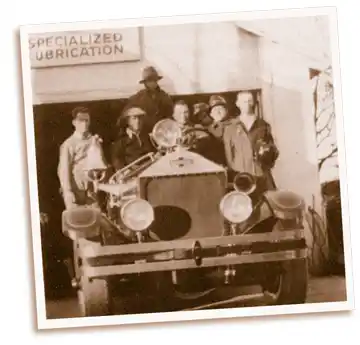

Out toward the western edge of town, past the lodge and the church, there was Horace Evans’ garage. Robinson remembered him as a right sort — the kind of mechanic who’d clean a sparkplug, rather than just sell you a new one. A bit further along, as Cobb recalled, there’d been Herbert Evans’ grocery (and shoe store) in the somewhat dilapidated building due west of Shop of the Four Sisters, and an auction house behind the grocery. And all the way out at White’s Neck Road, where there was once a gas station and now the Millville Pet Shop, Cobb remembered it as Lester Kauffman’s Studebaker dealership — and before that, his tractor showroom.

Out near the western edge of town, Debbie Evans runs the Miller’s Creek gift shop in the same building, built in 1947, where Richard Wood and Wilbur Hocker opened their hardware store. And Franklin Bennett continues to keep the family tradition alive at J.S. Bennett & Sons (truck and trailer rentals and towing), now in its third generation. John Swainey Bennett got his start in the area at Horace Evans’ garage, and transitioned to his own shop in the early 1930s. Bennet had started out building truck bodies for hauling poultry, according to his daughter, Betty Evans. A century in perspective As Wolfe summed it up, “it was a different time, a different life.” Isolated, but in many ways, she suggested, early Millville had offered as good a life as a person might hope for, even today. “There were a lot of things we didn’t have, but we didn’t know any better — so we didn’t mind,” Evans reflected. Not everyone had cars, but those who did shared them, Cobb remembered, and they didn’t hesitate to pick up children walking to Lord Baltimore (especially if it was raining). “It was a very small, wholesome, rural town,” Phillips added. “It was laid-back — the whole town, the whole system. I loved it.”

Millville’s story may be the story of every town. They struggle upward from the forest floor, and their citizens pour their labor into them, that they might grow strong and straight.

Millville has grown slowly over the past century — the U.S. Census of 1910 found nearly 200 men and women living in town, and nearly 100 years later, that number still hadn’t reached 300. But whatever changes come, the town will always have that slow century for its heritage — a solid start toward a noble maturity.